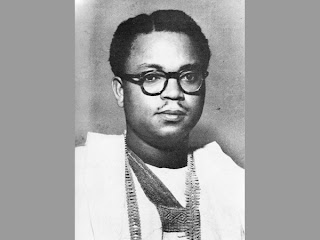

Anthony Enahoro was still a teenager when, in the early 1940s, he became the chairman of the Lagos chapter of the Nigerian Union of Students. By the time he turned thirty, the Kings College, Lagos alumnus had edited two newspapers, published a third, gone to prison thrice, founded a political party (The Mid-West Party), and won election into the Western Region House of Assembly. Enahoro’s activist leanings were deeply inspired by famed nationalist Herbert Macaulay, who founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), Nigeria’s first political party, in June 1923 (barely a month before Enahoro’s birth).

On March 31, 1953, four months shy of his thirtieth birthday, Enahoro moved a motion calling on the Federal House of Representatives to “[accept] as a primary political objective the attainment of self-government for Nigeria in 1956.”

It was an audacious move, and even though it ended up being merely symbolic at that time (it was never voted upon; the Sardauna of Sokoto, Ahmadu Bello immediately sought an amendment to the motion, asking for the replacement of “in 1956” with “as soon as practicable”; and another parliamentarian, Ibrahim Imam, moved a motion for adjournment of the sitting), it set in motion a series of events – including the adoption of a new constitution – that propelled Nigeria towards independence. (In 1957 the Eastern and Western regions attained the self-government Enahoro had clamoured for).

In 1954 Enahoro became the Western Region’s Minister of Home Affairs (later expanded to include the Mid-West region), and in 1959 he oversaw the foreign affairs portfolio in the shadow cabinet of the Action Group. In 1958 he led the Action Group delegation to the inaugural All African Peoples’ Congress in Accra, Ghana. He had been a founding member of the Action Group in 1951, and its pioneer Assistant Secretary, and in 1958 became its Deputy National President.

Enahoro played an active role in negotiations with the British government, in the final days of colonial rule. He was thirty-seven when his lifelong dream of Nigerian independence came to pass. Few would have guessed that an even more colourful life lay ahead of him.

Prison as school

Political scientist Richard Sklar has quoted Enahoro as saying that “prison was my school”. His first enrolment in that ‘school’ was at the age of twenty-two, when, as editor of the Nnamdi Azikiwe-owned Daily Comet, he was convicted of publishing an article deemed seditious by the colonial authorities. That first prison stint lasted nine months.

A year later he was back in ‘school’, this time for delivering, in Warri, a speech regarded as seditious. He spent twelve months in prison. His association with the Zikist Movement (described by the political scientist Richard Sklar as “the angry young men of post-war Nigeria”) soon landed him back in ‘school’ for a third stint.

Prison would beckon again more than a decade later. By this time the journalism days were behind him, and Enahoro was an established politician. Turmoil within the Action Group had led to the imposition of a state of emergency on the Western Region in May 1962. Months later the Federal authorities announced the discovery of a plot to violently take over the government, and filed felony charges against thirty-one persons. Enahoro was one of the accused, alongside Obafemi Awolowo, Lateef Jakande, and Alfred Rewane.

Fugitive offender

In September 1962 Enahoro fled Nigeria, first to Ghana, and then London, where he was arrested by the British authorities, charged to court under the Fugitive Offenders Act of 1881, and detained at Brixton prison. In England he became, in the words of the journalist Walter Schwarz, a “cause célèbre”: his case was vigorously debated in court, and in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Eventually, the House of Commons turned down his asylum request, and in March 1963 he was extradited to Nigeria. Once again, he had fallen on the wrong side of British law.

From prison to power

To worsen matters, the Nigerian government disallowed his lawyer, Englishman Sir Dingle Foot, QC, from entering Nigeria to defend his client, despite prior assurances to the contrary. In September 1963, Enahoro was convicted of treasonable felony and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. (A week later Obafemi Awolowo was handed a ten-year sentence). On appeal, Enahoro’s term was reduced to ten years.

However, Yakubu Gowon threw open the prison gates after taking power, following the July 1966 coup. Soon after he appointed Enahoro as Nigeria’s Federal Commissioner of Information and Labour under his Military Government. Enahoro served in that position during the civil war years, and until 1974. He later served as Federal Commissioner for Special Duties. The assassination of Murtala Mohammed brought an end to his stint in government. During the second republic Enahoro belonged to the ruling party, the conservative National Party of Nigeria (NPN).

Back to the trenches

The activist streak that first showed itself in his teenage years never left Enahoro. When it became clear that military President Ibrahim Babangida had no intentions of handing over power to a democratic government, Enahoro was one of the loudest voices of opposition, establishing the Movement for National Reformation (MNR) as an activist platform.

When Abacha began his reign of terror, Enahoro was at the forefront of the formation, and leadership, of the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), which would turn out to be the most potent Nigerian opposition platform of that era. He went into exile in the United States in 1996, to escape Abacha’s murderous rage.

When he returned to Nigeria in 2000, it was not to retire. At a rally in Lagos to mark his return, the then 77-year-old said: “We must not fear radicalism or radical ideas. If you agree with my vision of Nigeria as a nation of nationalities, then surely we must see that the future lies in Nigeria becoming a union of nationalities.”

In 2003, he founded the National Reformation Party, and served as its National Chairman until he died. He founded, with Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, the Pro-National Conference Organisations (PRONACO), which organised, in 2005, a ‘Peoples National Conference’ as an alternative to the Federal government’s ‘National Political Reform Conference’.

When he died last Wednesday, Enahoro was one of last three amongst his generation of nationalists. He lived to see an independent Nigeria turn fifty. Tragically, however, that independence remained largely nominal; the nation he and several others had fought so passionately for lays beholden to corruption, dismal leadership, and the continued subjugation of ethnic minorities.

Enahoro wrote an autobiography, ‘Fugitive Offender’ (1965), and was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Benin (1972), and a national honour, Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (CFR) in 1982.

Anthony Eromosele Enahoro, journalist, nationalist, administrator, traditional ruler, pro-democracy activist and renowned orator, died in Benin City on Wednesday December 15, 2010 at the age of 87. He is survived by his wife, Helen, and children.Source:http://234next.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment